‘By and For the People of Melbourne’: Establishing the Future of Public Health

A lot has changed in Melbourne in the last 100 years. And as Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation celebrates its centenary year, we look back at the origins of this visionary Melbourne organisation and discover a city not unlike our own.

Lord Mayor’s Fund for Metropolitan Hospitals and Charities is officially launched at Melbourne Town Hall by Acing Premier Sir William McPherson and Lord Mayor Sir John Swanson on 14 June 1923. SOURCE: Sun News Pictorial, 15 June 1923.

In the early 1920s, Melbourne was recovering from the influenza pandemic, which had killed 15,000 Australians and caused ongoing health difficulties for thousands more. The First World War was over, but as soldiers returned home – sometimes years after the war’s end – they brought with them the many health troubles and traumas of war.

Melbourne’s hospitals were bursting at the seams. At the Royal Melbourne Hospital, balconies were used as makeshift wards, and high demand coupled with inflation saw health costs spiral. In the five years from 1918 to 1923, maintenance costs for hospitals shot up by 50 per cent, and funding was never certain. While today we take state health funding and Medicare for granted, for most of the twentieth century, hospitals relied on charity to keep the lights on.

In the early 1920s, balconies at Royal Melbourne Hospital become makeshift wards. Lord Mayor’s Fund for Metropolitan Hospitals and Charities was established at a time when hospitals were inundated, and maintenance costs ever increasing. SOURCE: Royal Melbourne Hospital Archives.

Melburnians were generous donors, but collections could be haphazard. Aside from regular Saturday and Sunday appeals in churches, hospital funding was scraped together however possible – from workplace whip-rounds, to ‘tin rattling’ collectors up and down Bourke Street.

But in 1923, the city took a major step forward. The Lord Mayor of Melbourne, Sir John Swanson, assembled a committee of councillors, philanthropists, business owners and hospital staff to address problems around hospital fundraising for good. On 14 June, the office of the Lord Mayor’s Fund for Metropolitan Hospitals and Charities was officially opened to the public. Today, that organisation has become known as Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation.

"Day by day, I see greater possibilities in the scheme," Swanson said at the time. "It is not unreasonable to forecast through this great organisation an income sufficient for the maintenance of our charities."

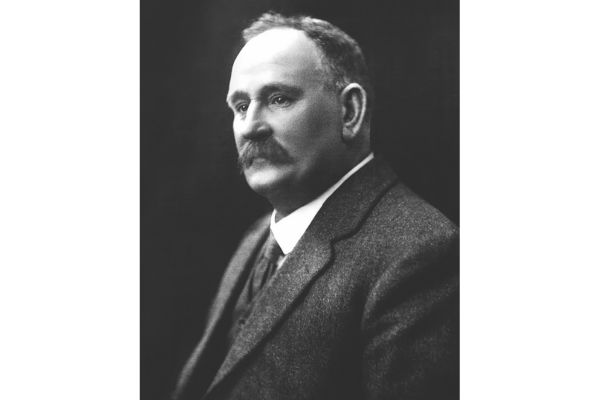

The Right Honorable Lord Mayor Sir John Swanson established Lord Mayor’s Fund for Metropolitan Hospitals and Charities. He was the Fund’s first bequestor upon his death in 1924, leaving £500 which formed the Fund’s endowment. SOURCE: Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation Archives

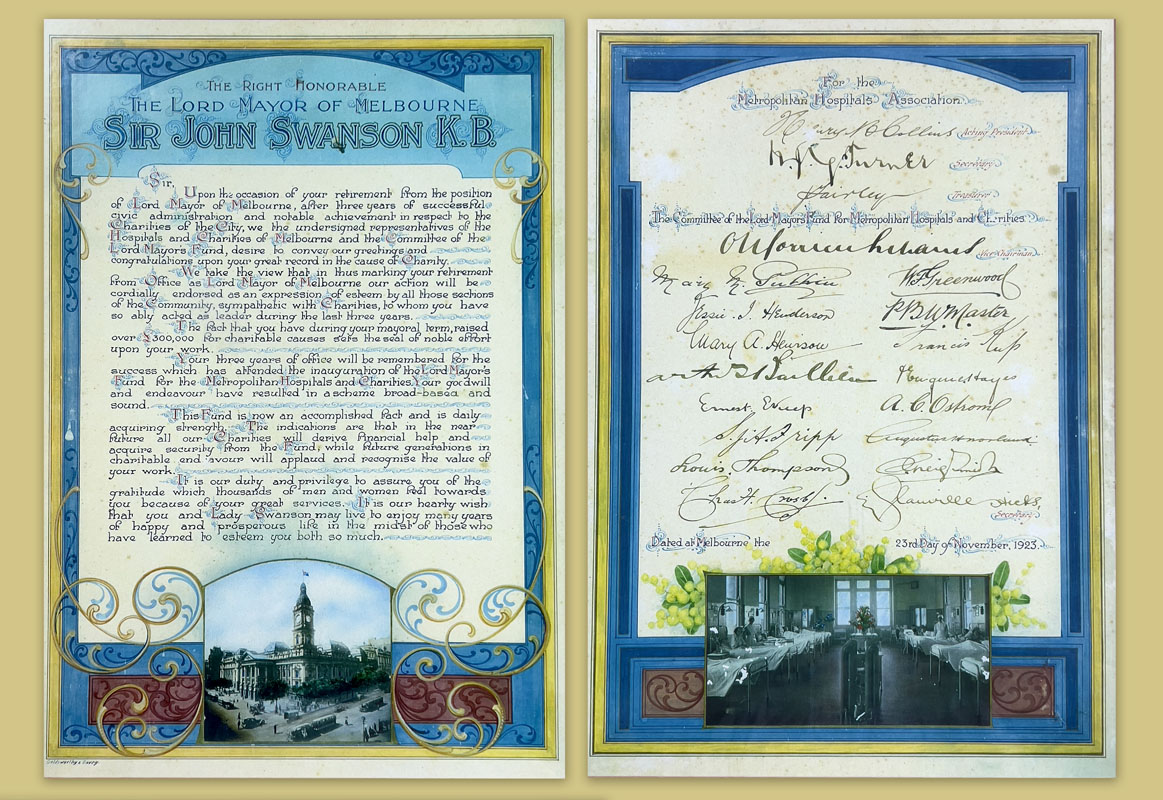

During Sir John Swanson’s three years in office, £300,000 was raised for charitable causes. He was presented with this certificate of appreciation, signed by the Fund’s inaugural Committee at his retirement. SOURCE: Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation Archives

For Dr Catherine Brown OAM, Chief Executive Officer of Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation, Swanson’s position was nothing short of visionary. "Sir John Swanson saw that there was a gap in services, and he sought to fill it. It’s underpinned by this egalitarian idea that everybody should be able to receive top-class medical services," says Dr Brown. "Now, that’s something Melbourne is famous for."

Dr Brown says there are now foundations like this all over the world. "If a city has a community foundation like ours, they are building up their ability to adapt to whatever comes along," she says. "It’s a kind of community insurance."

The calculations behind the initial founding of the organisation were simple: from an estimated 244,000 wage earners in the metropolitan area, Swanson projected that if each individual were to donate 2 pence (about a dollar in today’s money) per week, that would bring in over £100,000 a year. That was more than enough to meet hospitals’ basic needs, and would also leave hospital committees free to focus on managing funds rather than raising them.

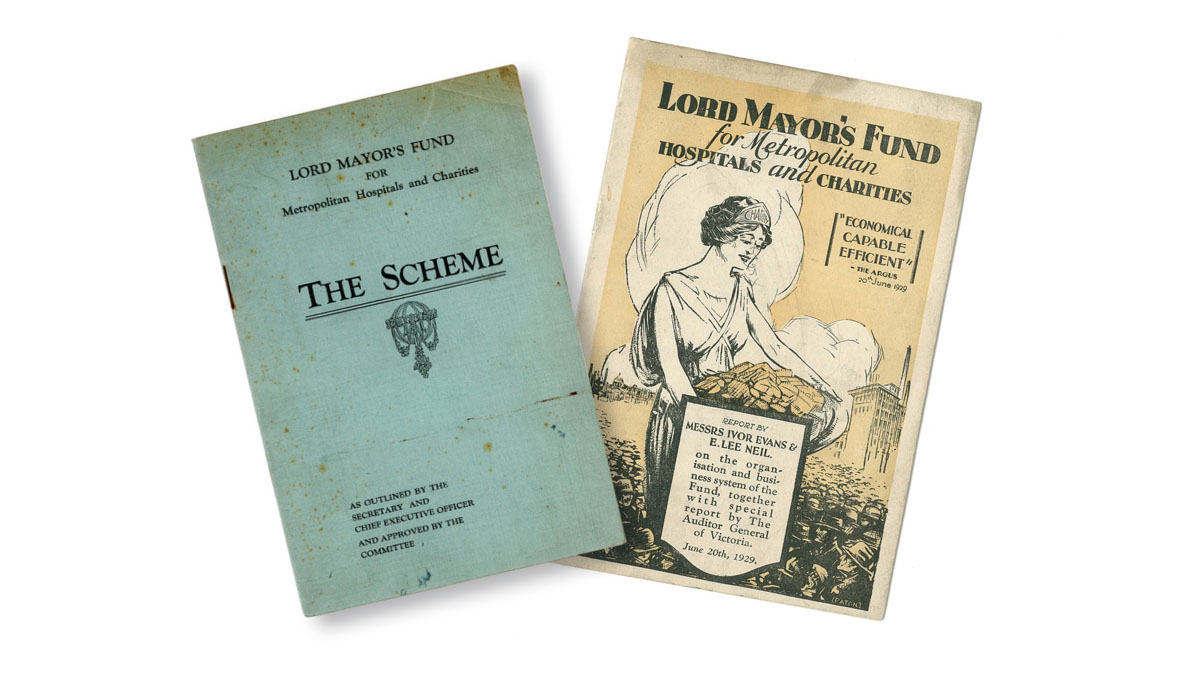

Early pamphlets produced by Lord Mayor’s Fund: "The scheme represents every man’s duty and every man’s privilege. Those who are in enjoyment of good health should think of those who are not. You, or your family, or your friend, may need the assistance of the Lord Mayor’s Fund tomorrow." SOURCE: Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation Archives

Contributions were not mandatory, but people were urged to contribute on a means basis. Those on higher incomes were asked to give more, and women, most of whom were on considerably lower incomes, less.

A flyer was distributed calling on the community’s sense of charity: "The scheme represents every man’s duty and every man’s privilege," it read. "Those who are in enjoyment of good health should think of those who are not. You, or your family, or your friend, may need the assistance of the Lord Mayor’s Fund tomorrow.

"You can afford 2 pence per week at any rate. Live up to this idea of true citizenship."

Racing and sporting clubs were approached, as well as business, factories, retail shops, theatres and music venues. Nominated representatives from these groups could drop money directly to the Fund’s offices on the ground floor of the Town Hall on Swanston Street, via an unassuming doorway the Argus referred to as a ‘hole in the wall’.

For 65 years, the office of Lord Mayor’s Fund for Metropolitan Hospitals and Charities was located at Melbourne Town Hall with direct access to Swanston Street from 1923 – 1988. The Fund’s office was a central, convenient location to receive the many cash and cheque donations from the public and acted as a base on street appeal days held by the Fund as well as other philanthropic and charitable organisations. The office also operated as the Melbourne City Information Centre for citizens and visitors and was manned by the Fund’s staff. SOURCES: Annual Report 1923; The Argus, 15 June 1923; The Herald, 24 Nov 1932.

With contributions sought from all corners of the community, the activities of the Fund quickly spread across the city. Posters adorned trams. Movie theatres held charity screenings and film festivals, and the newly refurbished Athenaeum Theatre donated its opening night takings. Community footy games raised money. The bands of the visiting squadron of the British fleet took over the MCG for a night. Donors listed in the Fund’s first annual report include some of Melbourne’s most prominent (and most enduring) names, like GJ Coles and Carlton and United Breweries, right down to individuals offering a few dollars.

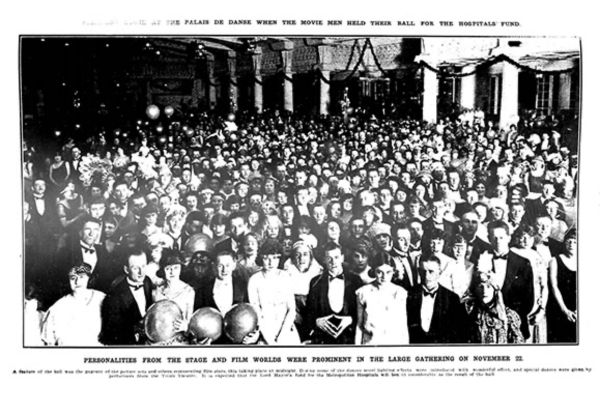

Over 800 people attend the ‘Movie Ball’ held in aid of Lord Mayor’s Metropolitan Hospitals Fund. The ball was hosted by the moving picture industry and held at the Palais De Danse, St Kilda on 22 November 1923.

Melbourne institutions like Coles and Myer, as well as the Railway and Tramway Authorities, were among the many supporters of Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation throughout the decades. SOURCE: State Library of Victoria

Melbourne institutions like Coles and Myer, as well as the Railway and Tramway Authorities, were among the many supporters of Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation throughout the decades. SOURCE: The Herald, 16 October 1942.

Melbourne institutions like Coles and Myer, as well as the Railway and Tramway Authorities, were among the many supporters of Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation throughout the decades.

A modest list of beneficiaries was initially drawn up – eighteen hospitals and healthcare organisations across Melbourne. But the Fund soon broadened its scope in response to community demands that the money be used more widely. By the end of the Fund’s first year, beneficiaries included eighty-four hospitals and medical charities. By the end of the 1920s, that list had expanded to over 200, including dispensaries, medical research groups and the Victorian Civil Ambulance Service.

Shortly after the Fund was underway, John Swanson passed away. In his will, he left the Foundation’s first bequest, a legacy of 500 pounds. In its first year, the Fund raised a staggering £25,797/1/3 (about $2.2 million today), and distributed the same, to the penny. By the second year, it hit £40,993/15/1. The impact of Swanson’s work was already clear.

With hospitals relieved of fundraising activities, money raised could go straight to patient care. More money was freed up for the growing field of medical research.

Since then, the Fund has kept growing and diversifying. It’s changed its name and been through some administrative changes – the development of Medicare and government funding for public hospitals means hospitals and patients no longer rely entirely on charity, for example. But today’s incarnation of Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation proudly continues Sir John Swanson’s vision as an independent collective giving fund, a century on.

Since its inception, Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation has continued to evolve to meet the community’s needs. Pictured above is the 1925 Executive Committee of the Lord Mayor’s Fund for Metropolitan Hospitals and Charities. SOURCE: Annual Report 1925.

Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation Board Members pictured with guest speakers, the late Peter Hero (front, centre), Richard Fahey (front, third from right) and Dipender Saluja (front, far right) at the Social Investment and High Impact Philanthropy Conversation held in 2013. SOURCE: Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation Archives.

Melbourne has come a long way, but today we face new challenges. For Dr Brown, a strong charitable sector means a strong community. Certainly, Sir John Swanson couldn’t have anticipated the complexities facing the city today.

"There are issues like affordable housing, which we’ve been working on for a decade," says Catherine. "Economic inequality has grown. Climate change isn’t going away. And then the COVID-19 pandemic arrived. We’ve been dealing with all of these at once."

Construction of 39 affordable housing units underway in Preston as part of Lord Mayor's Charitable Foundation Affordable Housing Challenge. The Challenge offered a $1 million grant for affordable housing, asking local governments to put forward sites and community housing providers to put forward housing concepts. City of Darebin and Housing Choices Australia co-developed the Preston site. The Victorian Government has also since made a significant Big Housing Build grant to support this project.

Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation provided a Grant of $150,000 in 2017 to support the Climate Council’s Cities Power Partnership program, encouraging communities to take action at a local level. Over 175 local government areas, comprising of over 500 cities and towns have joined the initiative and committed to supporting their local community's transition to clean energy. SOURCE: Climate Council

A grant of over $299,000 to Victoria University funded research on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our healthcare system. The results were sobering with over 60% of healthcare workers reporting anxiety and burnout, and many noting a desire to leave the workforce. Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation also supported the next phase, the development of responsive and sustainable solutions to address mental health impacts on frontline healthcare workers. SOURCE: Alfred Hospital.

The Fund (now Foundation) has adapted and responded to the ever-shifting landscape accordingly. For example, innovation grants (seed and scaling via public application) and also proactive grants, which invite applications to fund innovative organisations, including university researchers, community housing and health services and disaster relief. Last year, the Fund distributed $12 million in grants across Greater Melbourne to charitable and not-for-profit organisations.

"To keep supporting the charitable sector through all that, so the sector can support the Melbourne community, has been quite demanding. But it’s the reason we are here. We’ve had to be adaptable, listen to what’s going on."

Dr Catherine Brown OAM

Despite a century of change, Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation remains committed to the same promise. "We’re here to help Melbourne through the big challenges of the day," says Catherine. "We pool resources to tackle big problems. That still underpins everything we do."

"It’s strange to think that it’s so consistent, over 100 years. It’s in our DNA."

In 2023, as we celebrate 100 years of Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation, we’ll be looking back at a century of giving – from workplace giving, to community immunisation programs, its annual Flower Day Appeal, and world-class medical research.

But we’re also looking forward, just as Sir John Swanson did a century ago. "It’s important to think about the next 100 years too," says Catherine. "We might solve many these issues, but new ones will continue to emerge. The Melbourne community will need to be resilient. But Melbourne knows it has the Foundation behind it no matter what."